The green line was my planned route. The red line is what I actually did. Read on to hear my tale of woe.

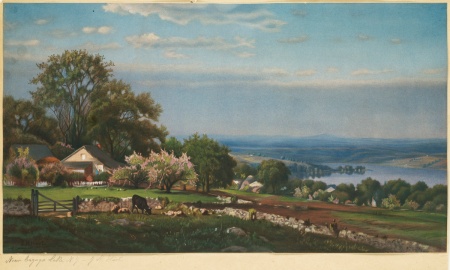

My new home of Ithaca is freshwater sailor’s paradise. Sitting on the southern tip of Lake Cayuga, there are at least three marinas within city limits. But finding my own path to the water was surprisingly difficult.

Here’s the problem: All of Ithaca’s marinas are located along a narrow, mile-long inlet—a partially manmade channel, as far as I can tell–that extends from the southern end of the lake and into the western edge of the city. It’s a bustling waterway; sailboats line docks, rented canoes and kayaks wander about with aimless enthusiasm, and a large tour boat embarks on regularly scheduled trips into the lake. But when I started calling marinas, looking for a place to park my trailer and launch my boat, I was turned away. The inlet, I was told, was too narrow to sail and the lake was too far away to paddle. Because I didn’t have a motor, I would have to take my boat elsewhere.

I continued to make calls and eventually reached the very friendly owner of one the town’s scruffier boatyards. He listened to my dilemma and suggested that I try launching from a state-owned marina near the mouth of the lake. The park’s boat ramps were still in the inlet, he explained, but closer to open water; maybe I could sail out from there. As for storing the boat, he had space in one of his open sided sheds and would give me a late season discount. I gratefully accepted his offer, checked this problem off my moving to do list, and continued packing up our Pennsylvania home.

We moved like Okies. My wife drove our good car with two vomiting cats, my oldest son drove the unreliable Subaru station wagon, and I followed in the U-Haul—with the sailboat hitched behind. We moved slowly and stopped often, but arrived safely.

By our second day in Ithaca I had the boat tucked away at the boatyard and for the next two or three weeks I was fully occupied by the excitement of exploring our new town. Even outings for the most prosaic reasons—groceries, gas, shower curtains—were infused with a sense of adventure. With road map in hand, we would find our way to the supermarket, the hardware store, the downtown shopping district, exclaiming like tourists in a foreign land as we explored each.

But once our furniture was arranged and our suitcases unpacked, I began to think about the boat. I knew that I should sail. Summer was nearly over and the long New York winter would soon begin; it would be wrong to let the season pass. Yet I hesitated. Publicly, I blamed my delay on work or the weather. Privately, I acknowledged that I was intimidated by my new homeport.

Sailing on Pennsylvania’s Lake Nockamixon was like playing in the little leagues; we were all amateurs and the lake was small. But this was the big time. Lake Cayuga felt massive and many of the boats docked around town represented the “A” list of America’s nautical heritage. In Pennsylvania, I received accolades simply because I was the only wooden boat on the water, but here I competed with ocean going keelboats, restored Chris-Craft cabin cruisers, elegant cat boats, and a half dozen other vessels ready for the cover of Wood Boat magazine. I suddenly felt like a country kid coming into town with a torn suitcase and straw in my hair—hot stuff back home, but an object of derision in the big city. All of my insecurities emerged and I worried about launching my boat in front of people with years of real sailing experience.

But I couldn’t delay forever so I picked a sunny day with light winds. With my teenage twins, I picked up the boat, towed it a mile to the state marine park and surveyed the scene. Because it was also a weekday, I had hoped for an empty boat ramp and no witnesses. But to my dismay, the waterfront was a hive of activity. Several ramps were occupied with arriving or embarking powerboats as onlookers sat on the grass and park benches. My heart sank as I realized that my launching would be a public event.

Small problems cropped up right away. Not until I started raising the mast—a task I complete while the boat is still on the trailer—did I realize that a turnbuckle was missing. It probably unwound itself and fell off during the drive to New York, but it had to be replaced before I could secure the mast and get underway. While the kids waited by the boat, I drove to a nearby hardware store (making a few wrong turns down unfamiliar streets) and bought a new one. Back at the boat, it took at least half an hour to put it all together.

By now it was a hot, cloudless day. Jumping on and off the boat from the steaming parking lot exhausted me and by the time the mast was finally raised, I was covered in sweat. Already tired, I backed the trailer—somewhat inelegantly—down the ramp and, with help from my kids, quickly pushed the boat into the water. After parking the trailer, I jumped aboard and announced that we were ready to go.

That’s when the second problem became obvious. In my rush to get going, I forgot to install the rudder, which I had removed from the transom before the move. While the boat started drifting away from the dock, I threw myself into the cabin, pulled out the rudder and pounded it into place while leaning so far out of the boat I nearly tumbled into the water. Even under ideal conditions, I often struggle to attach the rudder and normally use a hammer to fit the pins into the homemade hinges. Without tools, I accomplished the task with a bare fist and adrenaline. I collapsed into the boat with a sore hand and a shaking arm.

Still, there was no time to rest; we were in open water and I needed to raise the sail. So with my son at the tiller, I stepped forward and started hauling up the halyard and gaff lines as quickly as possible. And here, inevitably, was where the third problem emerged. Working too quickly, I let lines get tangled around pulleys at the top of the mast. The sail went up, but not quite all the way; it looked sloppy and the one real features of my boat—cool gaff rigging—was marred by the mistake. But I didn’t have time to drop the sail and straighten out the lines because the final and, ultimately, most serious problem was now becoming apparent: The wind had died and we were adrift.

Before setting off, my plan—such as it was—assumed that I could sail up the channel and into the lake proper, nearly a quarter mile away. At the time, I was not worried about the amount of wind, only it’s direction. Because I needed to head north, straight into the prevailing wind, I would have to complete a series of very short tacks, crisscrossing the inlet while heading upwind, like this:

I had never done this before, but I felt it was possible. I had read stories about sailboats much larger than mine “short tacking” their way up rivers and narrow waterways. But without wind, tacking–or any other form of controlled movement–now existed in the realm of idle speculation.

Waiting for the wind to pick up was not a solution either. Once we were on the water, I ruefully acknowledged that the inlet was probably too narrow for tacking in my boat and that I would be a hazard to navigation if I tried. With so many powerboats heading in both directions, any attempt to zig zag up the inlet while under sail would be like driving a very slow car back and forth across four lanes of Interstate traffic. As a plan, it was both impractical and dangerous.

By now, we had more or less drifted to the opposite bank. With my kids at the tiller, I grabbed a paddle with the immediate goal of avoiding the shore and the possible long term goal of paddling all the way to the lake. I don’t know why I thought this was possible; I was hot, thirsty, drenched in sweat, and a little bit sunburned. Clearly, I didn’t have the energy required to accomplish such an Olympian task. But I think I was motivated by a strong desire to get away from the boat ramp which, after all this time and effort, was still just a stone’s throw away. I imagined that a dozen eyes were watching our hapless struggle.

Digging into the water with my little paddle, the boat moved as if through glue. Time slowed and passing boats became an indistinguishable blur of movement. And this was when I hit the low point of my day—and of my sailing career to date. Amid my struggles, the captain of a passing motor boat hailed me from a short distance away and, pointing to my mast, said something that my brain could not properly process, but was definitely not a complement. In a tone of reproach, it sounded like “Your luff is loose,” or maybe, “Your halyard is hashed,” but in either case I knew what he was driving at and the note of judgment was clear enough. Because I was beyond rational thought and coherent communication, I simply paused in my paddling and offered him a weary shrug in reply. Inexplicably, he shrugged back and roared off.

I took this as a sign from God that it was time to give up. Having achieved both failure and humiliation—the twin horsemen of my nautical nightmares—I told my kids that it we should go home. Slowing, publicly, I paddled us back to the launch we had left only a short time before. Our total journey on our very first outing was about 200 nautical feet—and we never even reached Lake Cayuga.

I pulled the boat out of the water and solemnly drove it back its storage space in the nearby boatyard. I closed the cabin hatch, locked the trailer to a post, and drove away. And there it stayed until the following spring.

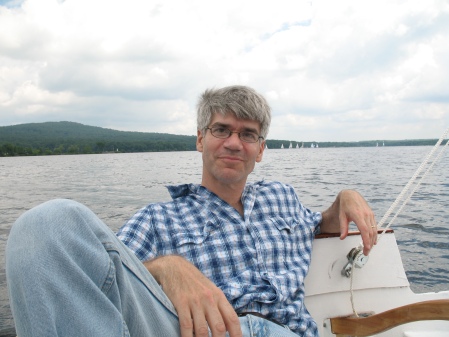

Posted by Paul Boyer

Posted by Paul Boyer